Members of the Cherokee Youth National Choir taking part in the installation of the Treaty of New Echota at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. (Paul Morigi/AP Images for the Smithsonian)" />

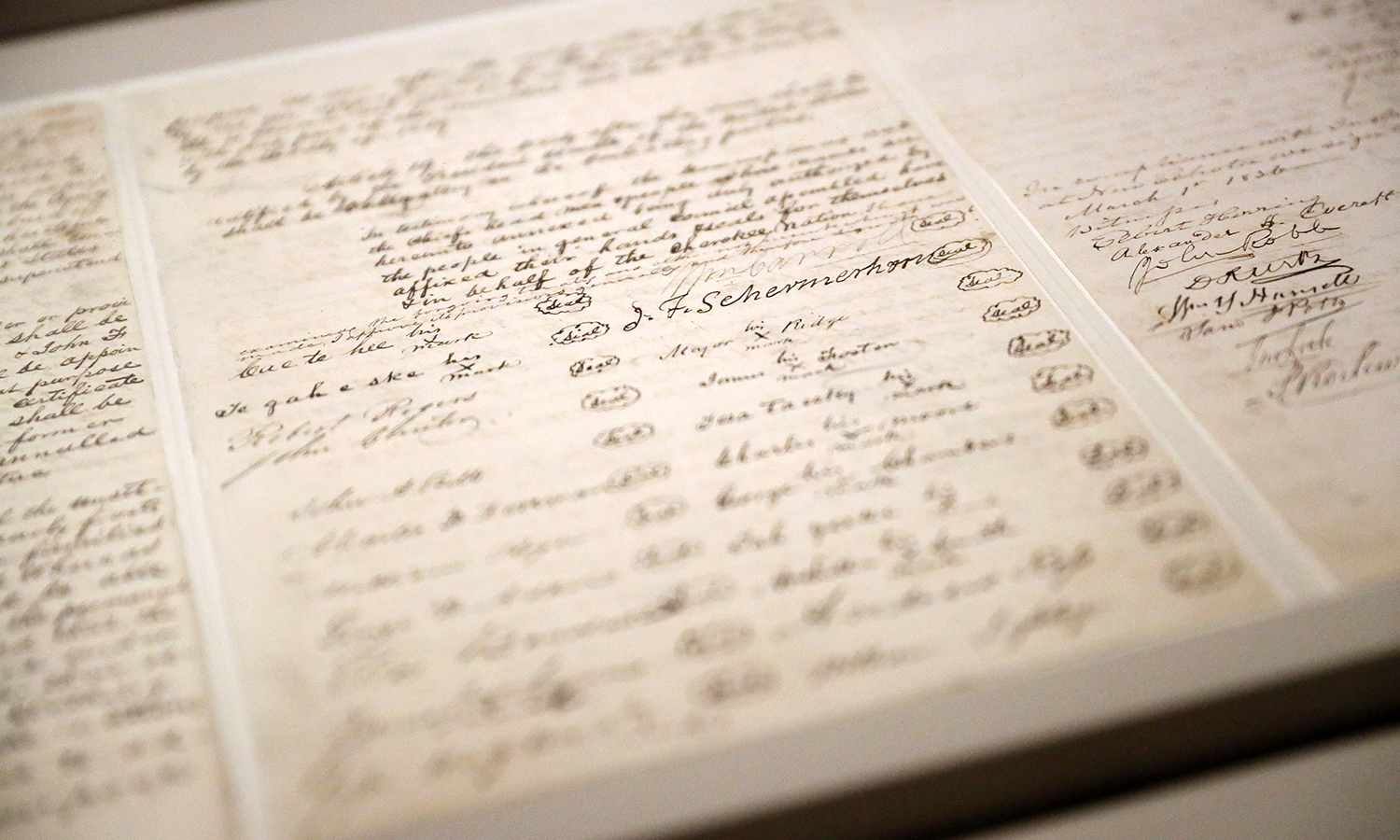

Members of the Cherokee Youth National Choir taking part in the installation of the Treaty of New Echota at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. (Paul Morigi/AP Images for the Smithsonian)" />Negotiated in 1835 by a small group of Cherokee citizens without legal standing, challenged by the majority of the Cherokee nation and their elected government, the Treaty of New Echota was used by the United States to justify the removal of the Cherokee people along the Trail of Tears. Representatives of the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes came together to see the treaty go on exhibit on the National Mall.

Members of the Cherokee Youth National Choir taking part in the installation of the Treaty of New Echota at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. (Paul Morigi/AP Images for the Smithsonian)" />

Members of the Cherokee Youth National Choir taking part in the installation of the Treaty of New Echota at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. (Paul Morigi/AP Images for the Smithsonian)" />

“The more we can tell our story, the less likely history will repeat itself.” —Principal Chief Bill John Baker, Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

On Friday, April 12, 2019, representatives of the three federally recognized tribes of the Cherokee people—the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma—came together at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., for the installation of the Treaty of New Echota in the exhibition Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations.

Negotiated in 1835 by a minority party of Cherokees, challenged by the majority of the Cherokee people and their elected government, the Treaty of New Echota was used by the United States to justify the forced removal of the Cherokees from their homelands along what became known as the Trail of Tears.

As early as 1780, Thomas Jefferson, then governor of Virginia, raised the idea of removing American Indians from their lands in the East. In 1803 President Jefferson wrote to the Indiana territorial governor that any tribe “foolhardy enough to take up the hatchet” against white settlement should be subject to the “seizing of the whole country of that tribe, and driving them across the Mississippi, as the only condition of peace.”

Native peoples resisted their displacement by every means available to them, including through public and political debate and in the courts. But with the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, Southeastern Indian nations faced enormous pressure to move west. A minority party of Cherokees concluded that their only course was to negotiate a removal treaty with the United States. With no authority to represent their people, the treaty signers gave up all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi River. In exchange the Cherokees would receive five million dollars and new lands in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The treaty, signed at New Echota, Georgia, in December 1835, established a deadline of two years for the Cherokees to leave their homelands.

A majority of Cherokee people considered the Treaty of New Echota fraudulent, and in February 1836 the Cherokee National Council voted to reject it. Led by Principal Chief John Ross, opponents submitted a petition, signed by thousands of Cherokee citizens, urging Congress to void the agreement. Despite the Cherokee people’s efforts, the Senate ratified the treaty on March 1, 1836, by a single vote, and President Andrew Jackson signed it into law.

Despite the United States’ ratification of the Treaty of New Echota, most Cherokees refused to leave their homes in the Southeast. As the 1838 deadline for removal approached, President Martin Van Buren—Jackson’s successor—directed General Winfield Scott to force the Cherokees to move west. Seven thousand U.S. Army soldiers rounded up Cherokee families at bayonet point. About a thousand Cherokees fled to North Carolina, where their descendants live today as citizens of the Eastern Band. Approximately sixteen thousand men, women, and children made the forced journey to Indian Territory. Some four thousand died on what became known as the Trail of Tears.

During the treaty’s unveiling at the museum, Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Bill John Baker pointed out that this chapter of American history could have turned out differently: “We lost by one vote in Congress to remain in our homelands.” Yet in Oklahoma and North Carolina, the Cherokees rebuilt their communities and sustained their traditions, institutions, and sovereignty. Tribal Council Member Richard French, representing the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, encouraged the three tribes to continue to work with each other. Chief Joe Bunch, whose United Keetoowah Band moved west of the Mississippi in the decades before the Treaty of New Echota became law, reminded the assembled guests that the Cherokees’ shared values have endured, saying, “Family, tradition, and language brought us here.” The Cherokee Nation Youth Choir closed the installation ceremony with a song in the Cherokee language.

Treaties—solemn agreements between sovereign nations—lie at the heart of the relationship between Indian nations and the United States. Sometimes coerced, invariably broken, treaties still define our mutual obligations. The National Archives holds 377 treaties between the United States and American Indian nations, with 100 available online. Since 2014, the National Archives has partnered with the museum to have treaties on display in Washington and New York City.

The Treaty of New Echota will be on on through September 2019 in Nation to Nation. Visitors to the museum can also see the exhibition Trail of Tears: The Story of Cherokee Removal, produced by the Cherokee Nation. The treaty installation coincided with the opening of the Cherokee Days festival April 12 through 14, hosted at the museum by the three tribes.

Dennis W. Zotigh (Kiowa/Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo/Isante Dakota Indian) is a member of the Kiowa Gourd Clan and San Juan Pueblo Winter Clan and a descendant of Sitting Bear and No Retreat, both principal war chiefs of the Kiowas. Dennis works as a writer and cultural specialist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.